A pleasant evening breeze whisked the soft smell of jasmines from the yasmeen el hindi trees as I was walking with Sina in one of Tagamo’s gated communities. Ramadan decorations were lighting up the houses on either side of the road. Sina and I were trailing behind the rest of the group because he was balance-walking on the edge of the narrow sidewalk that bordered the green island in the middle of the road separating the two lanes. Out of the blue, Sina asked me to tell him a story. I used to tell him and Amina stories all the time when they were younger, but it’s been a while since either of them have asked. We walked past one of the villas and the not-so-kid-friendly story that has been plaguing me lately immediately comes to mind. I point at the villa we pass and start improvising a child-appropriate version of the story.

It was a rather large villa with tall walls surrounding it. All the houses in that compound had walls, but they were puny compared to that one.* It was a house we had walked by many times before, always noting its walls and the spectacle of expensive-looking cars with distinctive license plates that often flanked them tall walls. We always guessed that someone important must live there. Probably someone involved in politics. And now I know exactly who it was.

Ibrahim El-Argany.

This past February was the first time that I was introduced to that name. And now I feel like I can’t stop thinking about that name and all the stories behind it. His is a complicated story that I stumbled upon because of what’s happening in Gaza. And Egypt’s role in it. I want to write down what I understand to be the story from the bits of the narrative that are scattered over the internet in articles and investigative reports and facebook and Instagram posts. I want to write it for for my kids to read when they’re older because I think it is an important and troubling piece of what is to become our history. A piece that can get lost in the chaos.

My memory of when this first began goes to reading a Mondoweiss piece by a Palestinian mother that ends with asking readers to contribute to her GoFundMe to help her cross the Rafah border. Right around that time, I had started hearing chatter about “the Egyptians” charging Palestinians exorbitant amounts of money to allow them to cross into Egypt and that article was the first time I came across that ask first-hand. My first instinct was to doubt or deny it as real. Or maybe it was real, but it couldn’t be systematic. Or institutionalized. Could it?

I remember texting my family on our whatsapp group and checking if anyone knew anything about this. I remember my dad replying saying he’d heard about it but wasn’t really clear on who was doing it. It definitely wasn’t the government though, he said. Just marginal unsavory opportunists unofficially profiteering from this crisis. That sounded both shocking and plausible. But more and more stories started popping on my instagram feed and it was harder to dismiss them as outliers. So when I was in Egypt, I asked again. My brothers this time. It was Salah who told me about the Lina Attallah piece on madamasr, which is an absolute gem of a resource. He was also the first to mention that name. Argany.

Ibrahim El-Argany is the person behind the business that monetized Palestinians’ attempts to flee the destruction being wreaked on them in Gaza now. He is a very powerful man in Egypt and the story of how he rose to power seems to be inevitably connected with Gaza’s.

Although Argany’s business empire is versatile, flaunting some 10 distinct divisions including money exchange, security, and agricultural development, it is built on three main pillars: construction, trade, and transportation. That’s where he first established himself back in 2010 with his Abnaa Sinai company.

I don’t know if he started his company with Gaza specifically in mind or if his business sort of happened upon the Gaza market by virtue of its proximity. At any rate, today, the fact that Palestine is an explicit market is openly advertised on their platforms: “Gaza is one of our main markets as we export and supply building materials, petroleum products, machinery and equipment as well as food supply.” This export business existed before the current assault and I guess it is not inherently evil. After all, Gaza needed the material, and someone needed to supply them so - I guess - kudos for him for servicing that niche community? Not quite palatable but such is life in our capitalist consumerist world, right?

This realist pill becomes somewhat harder to swallow when projected against the reality of what causes the destruction in Gaza. Every time an Israeli attack on Gaza destroys buildings and roads – 2012, 2014, 2021, 2022, the day after always involved rebuilding, which inevitably relied on some combination of Argany’s business web. So the Caterpillar machines Gazans would use to haul the rubble, the cement and steel they would need to rebuild their destroyed homes, the gas and diesel they would need to fuel all the machines, and of course the transport of all these goodies – machines, raw materials, and even commercial goods. All would come via Egypt through one or more of Argany’s companies.

That some specific company (or set of companies) are profiting from war and destruction already seems like it would create a perverse set of incentives for said companies. But I guess some company was going to have to be part of that and most likely they wouldn’t be doing it pro-bono, right? Once again, while morally uncomfortable to say the least, it’s not inherently wicked.

That realist pill becomes a downright choking hazard though when looking at one of the newer additions to that same warmongering empire – the one that has been recently garnering him with a lot of probably unwanted attention.

Hala Consulting & Tourism (not to be confused with Halla Travel) was established in 2019 to “facilitate travel visas and residency documents to ensure a hassle-free process” for Palestinians seeking entry to Egypt. When I first learned of this I could not at all understand how anyone would think to create this business because it implied a sense of callous normalcy to Gazans’ seeking entry into Egypt that ignored the glaring reality of their blockade and bombardment. It also casually and conveniently sidestepped the government’s role in that blockade, which Egypt is theoretically obligated to maintain under the 1979 Peace Treaty and the subsequent 2005 security agreement that was effectively suspended in 2007 after Hamas took power. How then is this private company claiming that paying a fee will allow Palestinians swifter passage into Egypt than that officially offered by the government? The government of course denies that this pay-for-passage model exists and labels any such activity as illegal. And yet still it continues. How? Either our government is complicit or impotent. I wonder which it is.

At any rate, when I read a little about how this Hala business started, it became less alien to my own experiences in Egypt. Still wholly unacceptable, but more familiar.

For starters, the whole service was marketed as tanseeq (تنسيق), coordination. Because of how much harder it was to cross the Rafah border after the new border security arrangement that came with Israel’s withdrawal from Gaza in 2005, and the subsequent fallout between the PA and Hamas after the latter won the elections in 2006, the border was now more often than not closed. And the whole process of getting permission to cross became a lot more bureaucratic. A Palestinian wishing to cross into Egypt would have to send their papers to the Palestinian and Egyptian authorities to authorize it, and Israel has to OK said authorization before they (the authorities) can grant them (the Palestinians) whatever stamp they needed to cross.

Stamping official documents in Egypt is no small feat. Any Egyptian who has had the pleasure of dealing with the labyrinthine Egyptian bureaucracy – whether by updating a job on their national ID, or changing their ID status from single to married, or issuing a birth certificate for a newborn – knows of the escapade that likely awaits them by going to a government building, figuring out the right floor (I’m thinking of ‘Abaseyya), wading through throngs of fellow citizens trying to figure out which unmarked window should they attempt to submit their request at. One can spend hours just to be told that they are missing a stamp on one of the dozens of papers they are carrying or maybe even that they are actually at the wrong building altogether.

This gets more complicated when dealing with papers from foreign jurisdictions. For example, to get my sons (both of whom were born in the US) Egyptian citizenship and an Egyptian passport, I had to have their US birth certificates authenticated by the Egyptian embassy in Chicago (which I did not know the first time around) and then they had to be translated at an authorized translation office in Egypt, then stamped at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs before I could submit them at ‘Abassiya.

None of this is simple , particularly when the requirements are not clearly or officially listed (at least they weren’t when I went through this) and so you go into it semi-blind. That’s why when last summer - after almost 2 years of trying to get Rawy’s paperwork in order (it took 2 years because I’m only in Egypt intermittently for limited amounts of time) - when I heard of a coordination service, I was intrigued.

This office claimed that I can just hand them a copy of the embassy-authenticated US birth certificate and they would get all the stamps needed. What’s even better was that they had an office that was 5 minutes away from my parents so I wouldn’t need to roam the various government offices scattered all over traffic-plagued Cairo, which would’ve been jam-packed with fellow frustrated citizens just to get them damn stamps. All I had to do was pay a service fee. (This is the exact type of service that I despise and typically avoid because it alleviates Egyptians with means from dealing with one of the last standing equalizers – the Egyptian bureaucratic experience - but I gave in knowing that there were other steps of the process that I still had to do myself).

I wasn’t really sure if the service offered was a real thing, but I decided to pursue it anyways. The fact that the tiny office, crammed with two desks that occupied some 85 percent of the space, was located in a half-abandoned mall in the middle of a construction site in New Cairo did little to alleviate my concerns. But I took a leap of faith and lo and behold some 10 days later the deed was done.

In the olden days, a similar sort of assist could have been given if you had the right connections or wasta (وسطة). So if say my dad had done a surgery for some Ministry of Interior official who happened to be in charge of one of the relevant government offices, when later I needed to get something done, maybe my dad would give him a courteous call explaining the circumstance and the official might suggest a time for me to visit the government building at which point he might notify one of his helpers to guide me to the official’s office where I would slip in and get the paperwork done. No windows no nothing. In return I would generously tip the helper guy and my dad would maybe owe the official a favor to be repaid sometime in the future.

In this scenario, people with relevant and relative influence coordinated to get the paperwork done more seamlessly. What this somewhat sketchy company (I’m not even sure if it’s officially a company) offered was an institutionalized form of this interaction and it too fell under the broader umbrella of “coordination”. One no longer needed to know someone special to get a leg up with the process. That company for whatever reason has an in with the relevant government agencies and so it sends an agent on my and other clients’ behalf to collect those stamps and signatures in bulk and then hand it back to me. As long as one had the money, they could get the same service.

I imagine a similar type of process is involved in processing the paperwork for Palestinians needing to cross into Egypt and it’s probably a lost worse. And I imagine the issue was less one of convenience and more one of urgency. So, naturally, unofficial coordinators who had some sort of sway with the relevant Palestinian and Egyptian agencies crept up and began doing the age-old job. Palestinians too are probably intimately familiar with this pay-for-passage model as is sadly depicted by Kanafani’s Men in the Sun with Palestinians in the 1950s seeking safe passage through Jordan and Iraq to get to Kuwait. So the idea, I’m sadly realizing, is not that novel on both sides of the border.

For the Rafah border, passage coordination reportedly began with a Palestinian woman formerly employed by the PA. She could allegedly get nearly anyone through. After seeing how lucrative that line of business could be, a few similarly sketchy hole-in-the-wall companies emerged, and they charged exorbitant amounts - as high as $2000 a person. When Argany’s Halla company entered the scene in 2019 with his $1200 charge, it seemed to be viewed as a stabilizing factor in this passage-coordination black market as it drove down competitors’ prices. At one point, prior to October 7th, Hala’s prices were as low as $350.

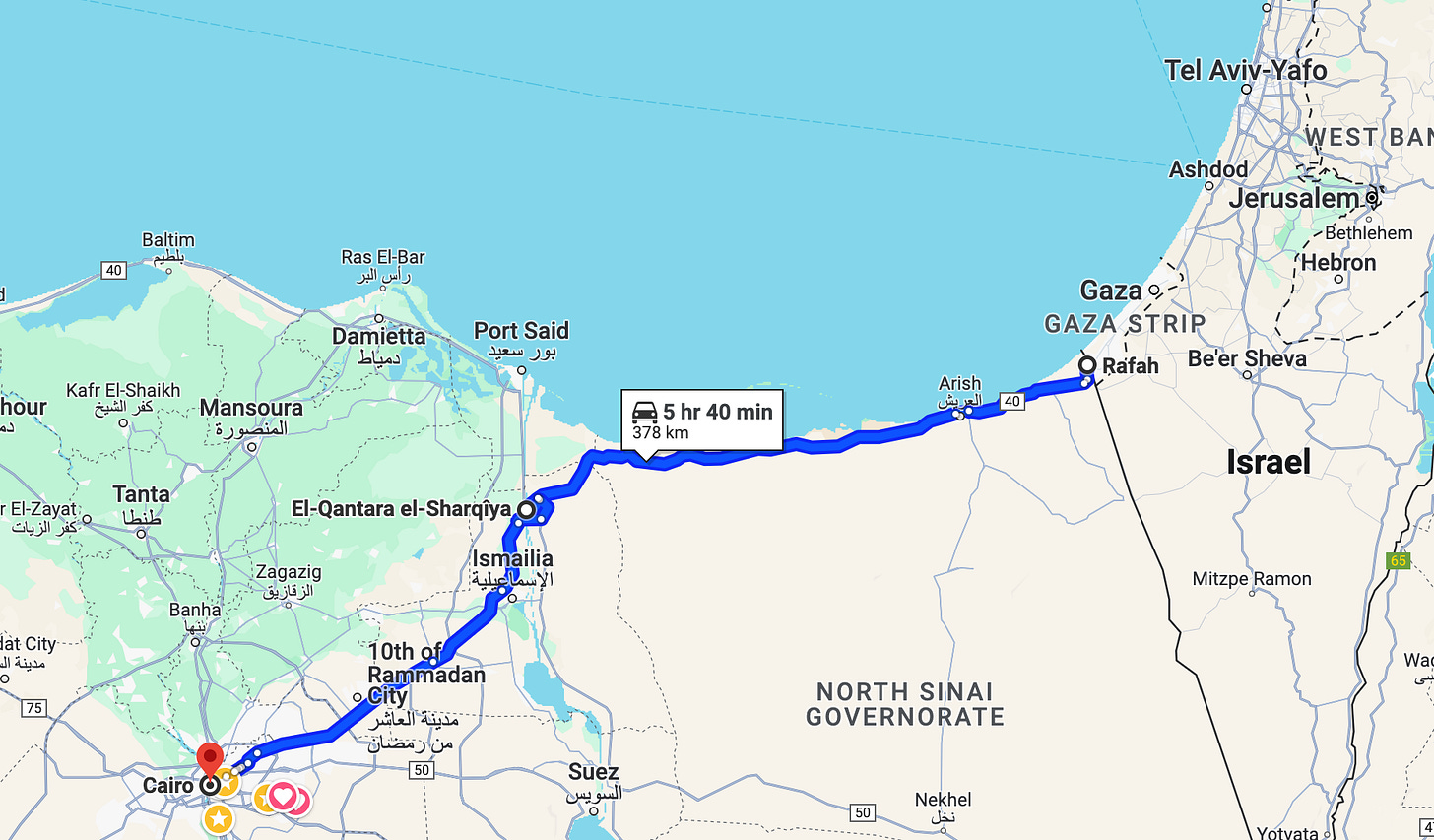

Hala also had advantages that others probably did not. It advertised a speedy trip from Rafah to Cairo along the coastal Arish/Bir al-Abd route. A trip that could otherwise take days because of all the checkpoints and security clearances, could with Hala take as little as 5 to 6 hours.

Once again, most Egyptians who have driven through Sinai (even Southern Sinai), know of the multiple checkpoints and the hassle entailed in needing to stop at each and every one, and depending on the whims of the stationed soldiers - typically young and probably serving their compulsory military service - having your bags checked and your IDs verified, especially if you are part of a group on a bus. This ordeal can be markedly stretched out if the passengers include foreigners because then they must wait for a police convoy to escort them through checkpoints, a requirement that could involve waiting in the blazing sun or alternatively in the middle of the night for hours till that convoy is ready to go. Often when my family drives through, we try to hide the fact that Cole is a foreigner by asking him to “blend in” or pretend he’s sleeping just to avoid the hassle of needing to wait for a convoy.

So I could see how Hala advertising a smooth speedy ride could be appealing to anyone, but especially Palestinians who are all too familiar with the implications of a checkpoint. Equally important though, because Hala institutionalized – they had a form for travelers to fill and a facebook page with contact numbers and office addresses both in Cairo and Gaza - an otherwise sketchy business that was prone to fraud, I can see how that offered an appealing option to Palestinians with very little choice. And so it was that Argany’s “tourism” business grew to monopolize the Rafah border passage market.

After October 7th, border passage came to a screeching halt. When it eventually returned, it was a free for all and it took a while for Argany’s company to reestablish its control. This time at exorbitant prices. Though it depends on whether the Palestinians had Egyptian passports, refugee travel documents, or had no other passports, now the passage coordination fee can be as high as $5000 per person. Which was when chatter around Argany and his profiteering from Gaza’s trauma started circulated.

The government of course denies that this pay-for-passage model exists and labels any such activity as illegal. And yet still it continues. How? Either our government is complicit or impotent because Argany’s business can’t be a secret to it. The very fact that he marketed his service as a secure and speedy trip from Rafah to Cairo, along routes that require security clearance, begs the question: how and why did Argany’s company get such clearance?

A little peak into Argany’s business and security affiliation with the army makes it easier to imagine how.

This is part one of a two-part piece.

*Correction: My parents tell me that the house I thought was Argany’s - the one with the tall walls - is actually someone else’s. Argany has 2 other houses one right next to it and another across from it. They’re not sure if he himself resides there or members of his immediate family - like his mother and wife.

Love reading these

Our students leading the encampment to divest at SFSU met with university president and provost. (I was there). Small and yet meaningful (and they were inventive and peaceful and well informed) resistance to the complexity of capitalism’s cashing in on oppression. Our university is in process of changing investment policy. Bigger beauty in m mind lives in how these us encampments are spotlighting current and historical and heartbreaking complicity.

Thanks for this nuts and bolts article about the corruption involved in crossing the Rafah border into Egypt. I look forward to reading part 2.